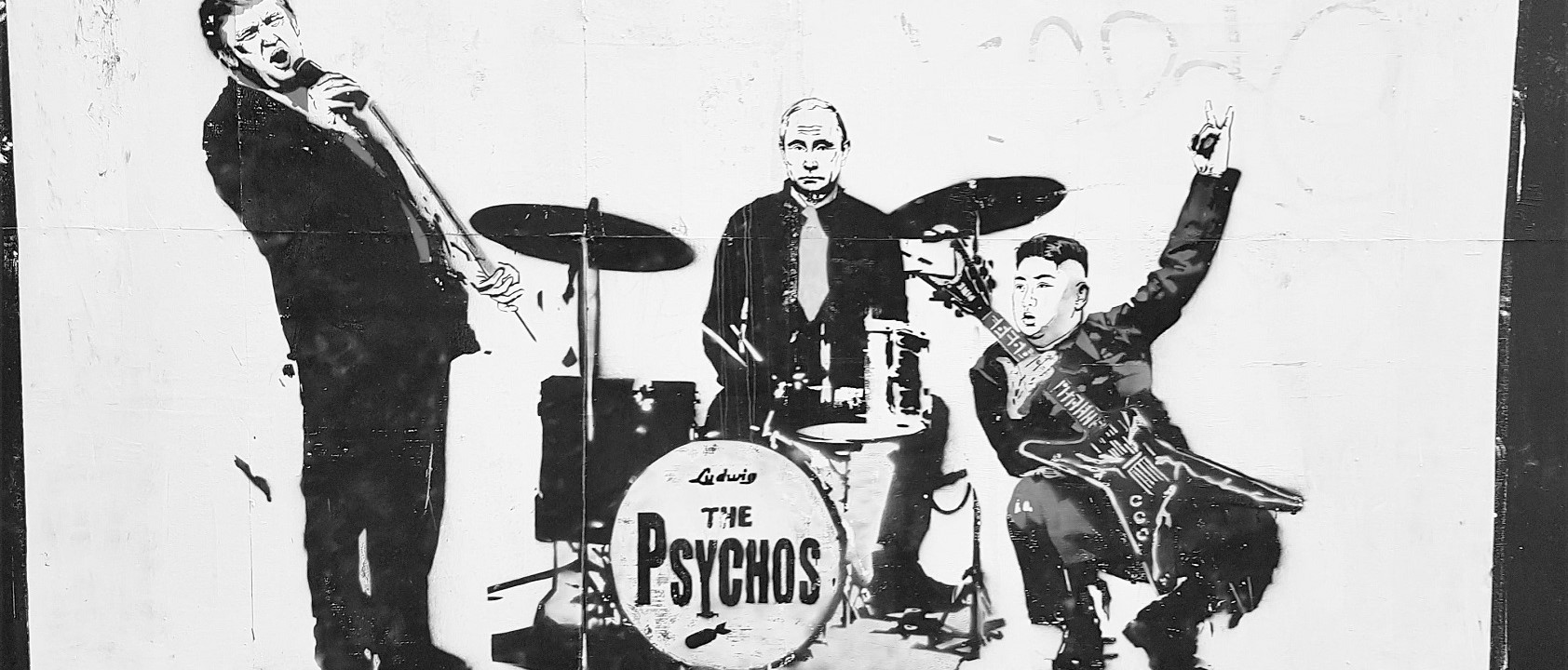

Men Behaving Badly

Share this article

Are the markets heading for the menopause?

“TMT, Too Much Testosterone. Way more dangerous than TNT.” ― Robert L. Slater, author.

The financial world does not have the greatest of reputations, especially in the wake of the recent financial crisis. Reckless behaviour both on and off the trading floor plastered all over the tabloid press, while the broad sheets analyse the intricacies of complex derivative trades that have gone sour. All the usual soap boxes blame all the usual villains; men behaving badly.

A report by Dr. Katherine Rake for the Fawcett Society, an organisation in the UK that campaigns for women's rights, even goes as far as to suggest that the recession was ‘man-made’. A new suspect has recently come to light, still male, but something that men can blame too.

Have you ever tried blaming a woman’s behaviour on her hormones? I wouldn’t recommend it; life is generally not worth living after such an observation. But according to John Coates, a senior research fellow in neuroscience and finance at the University of Cambridge and former trader at investment banks such as Goldman Sachs and Deutsche Bank, male hormones have a lot to answer for. Exaggerating financial market bubbles and crashes, any decisions made under stressed conditions as well as the well documented over the top behaviour traders are infamous for can all now be blamed on male hormones.

In his book, The Hour Between Dog and Wolf: Risk-Taking, Gut Feelings and the Biology of Boom and Bust, Coates has taken an in-depth look at the biology of risk. His research shows that men make bad decisions under pressure because of their hormones. Based on a study that Coates conducted in 2010, he found that traders had higher testosterone levels on days when they had higher than usual profits. He believes that with high levels of testosterone traders undergo a chemical “winner-effect”, a hormone-induced euphoric feeling fuelled by adrenaline and cortisol that stimulates dopamine in the brain, which in turn drives them to take even greater risks.

The addictive feel good hormone, a fight or flight relic from our prehistoric lives, is the driver of irrational behaviour of male traders or managers ‘behaving badly’ when the stakes are high. This is not really news, but what few realise is that after prolonged periods of stress, adrenaline and cortisol levels can become chronically elevated, and these male ‘Masters of the Universe’, to pilfer Tom Wolfe’s term, can turn into Cinderella at midnight if the markets go against them. Coates argues that this “Jekyll-and-Hyde transformation” into a risk-averse pessimist could be contributing to market crises.

As a wealth manager, we need to know about anything and everything that could affect a manager’s trading or investment ability, but behavioural economics, while new, is something we believe could be of relevance to the investment industry as a whole. “Traders, risk managers, and central banks cannot hope to manage risk if they do not understand that the drivers of risk taking lurk deep in our bodies. Risk managers who fail to understand this will have as little success as fighters spraying water at the tips of flames,” says Coates.

We will look at why Women Behave Better in finance on a broader level separately, but in this case women have roughly 10% to 20% of the testosterone levels of men, which drives them to operate in a different way to men (and not necessarily more risk adverse) but often with a higher performing outcome. Gender diversity by increasing the number of women running money and financial institutions is one of two solutions that Coates came up with to stabilise the financial markets.

But it is the second one, the biological diversity that could be achieved by hiring older men, whose testosterone levels decline at an accelerated rate after 50, that is an interesting one to consider further. It may be a less obvious solution but one that has a number of collateral benefits.

Men of this age are not only less susceptible to the hormone loops that mutate normal risk-taking into risky behaviour, but hiring them could help to solve another problem that is hanging over the asset management industry, namely the impact of the retirement of the ‘baby boomers’. Baby boomers—77 million or so born between 1946 and 1964—are retiring now, which according to J.P. Morgan Asset Management will have an impact on the economy, the markets and retirement planning.

In the US alone, the number of people turning 65 over the next decade will be about one million per year higher than the decade ending 2010, a J.P. Morgan paper stated. Baby boomers are the longest living generation, and they are the most productive. As this cohort retires many are, quite rightly, asking questions: will productivity lessen; will spending decline; will all their equity investments suddenly be turned into income earning assets? Will the demand for assets fall when the baby boomers retire? was a question that the US Congressional Budget Office asked back in 2009.

More importantly, if demand for equities is replaced by the need for fixed income could the retirement of these baby boomers—both male and female—cause the mature equity markets of the US and Europe to hit menopause? A recent article in the Wall Street Journal highlighting outflows from US 401(k) pension savings plans seems to be backing the menopause argument. Using data from Cerulli Associates’ annual report Evolution of the Retirement Investor, it would look like the US 401(k) system will become cash flow negative in 2016 as more retirees take money from their savings plans than they invest in them.

Other evidence, however, suggests tattoos, motorbikes and mistresses; more of an equity market mid-life crisis where financial advisers will create new and creative solutions, and retirees will spend in different ways; think cruises, cars and cottages. The mature economies globally are not as lively as their younger emerging counterparts anyway, but there are a number of other considerations to make when looking at the effects of the retirement of the baby boomers.

For a start, not all the retirement money will leave the pension funds at once; it is likely to get rolled over into individual retirement accounts as a way to simplify and aggregate portfolios. And even then, not everyone is likely to retire in the same year (there are 18 years between the oldest boomer and the younger ones). Secondly, the financial crisis wiped away the savings of many, so some retirees, those that can and want to, will continue to work. Thirdly, new investors will enter the markets, including migrants and the Generation X and Echo Boomers (children of the baby boomers), all of whom are likely to be investing by then.

One of the reasons (investment) life beyond the 401(k) is an interesting opportunity is that it is unchartered territory, one that has the potential to be driven by financial technology. Think robo-advisers that are now all the rage, helping investors make investment decisions with computer simulations. Today, you can even get artificial intelligence-driven investment managers with funds that are programmed to remove behavioural market dynamics such as biases and heuristics.

The potential for such fintech solutions to threaten the traditional advisory model is something we have looked at in greater depth separately, but what is important to note here is that advances in technology have been behind many of the bull markets such as those in the 1920s and the dot-com and TMT boom that burst 15 years ago (hormones just help to exaggerate the problem not create it).

There are some that believe that the next equity crash will be driven by the baby boomers dumping equities, but if Coates’ theories on the endocrine system and financial risk-taking being related have legs, then it might be worth looking at his diversity-driven solutions to build stable financial institutions. Could the hormone-driven longer-term thinking that women (and older men) have to offer really help mature markets in a mid-life crisis?

Photo: © Niki Natarajan 2018

Artist: Loretto

Article for information only. All content is created and published by CdR Capital SA. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s). Information on this website is only directed at professional, institutional or qualified investors and is not suitable for retail investors. None of the material contained on this website is intended to constitute an offer to sell, or an invitation or solicitation of an offer to buy any product or service. Nothing in this website, or article, should be construed as investment, tax, legal or other advice.

Related articles

The XX Factor

The Queen has reigned for 67 years. Communism has risen and fallen. The Beatles have come and gone, Britain is 5th most economically powerful nation. Women CEOs drive 3x the returns as S&P 500 firms run by men. Why is workplace inequality still a subject?

A World of Risk

“I violated the Noah rule: Predicting rain doesn’t count; building arks does” - Warren Buffett. Can you live in harmony with risk? The consensus is that if you can measure risk, you can manage it. But how do you pick which risk to manage?

Women Behaving Better

Explaining the differences between the sexes, especially if you are a man, is like playing with a loaded gun. Advances in neuroscience means attributing these differences to our brains being wired differently is both socially acceptable and good business.