Democracy - fair or flawed?

Share this article

Fair or flawed?

“It's not the voting that's democracy, it's the counting” ― Tom Stoppard

The UK’s vote to exit the European Union and Donald Trump’s victory were not simply signs of the demise of globalisation and the rise in populism; they were signals of a worsening ‘democratic recession’.

In 2016, the US government got a democracy downgrade from ‘full democracy’ to ‘flawed democracy’ according to The Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index 2016.

The related 2016 EIU report Revenge of the “deplorables”, stated that almost twice as many countries recorded a decline in their democratic score as recorded an improvement; of the universe of 167 countries covered, only 19 now qualify as a full democracy.

In 2017, the US is still a flawed democracy and ranks 21, just below South Korea. Only 4.5% of the world's citizens now live in fully functioning democracies. This is down from 8.9% in 2015.

So, what are democracy’s flaws?

The first is general voter ignorance. Brexit was a referendum not a General Election, and therefore with one person one vote, the outcome was always going to be binary. Would people have voted differently on Brexit had they realised that their vote counted? Perhaps.

In the US, a rise in level of education among the voters does not seem to have changed the general ignorance about politics and policies. Yet, 82% of those that voted for Trump said they would do so again.

Clearly something else was at play for such an outsider to win. And it wasn’t money: Trump spent $957.6 million compared to Hillary Clinton’s $1.4 billion on his campaign.

The exponential power of Trump’s dollar is fascinating, however. At $13.5 million, Robert Mercer of Renaissance Technologies, was Trump’s biggest donor. Not only that, but Mercer was also a financial backer of Cambridge Analytica, the new Emerdata¹ that has arisen from the ashes of Cambridge Analytica’s London offices, and the controversial right-wing news site Breitbart.

Maybe, as a senior executive at one of the world’s smartest hedge funds, Mercer realised the frailty of the democratic process and that we live in an age of the long-odds event.

Following the revelation that the Russians had used Facebook to stoke discontent and fuel the Trump campaign in the run-up to the US elections in 2016—recently evidenced by the publication of 3,519 Facebook advertisements—the Brexit malcontents cried foul and blamed the Russians² for influencing the EU exit outcome too.

Although, according to a UK House of Commons committee report, Lessons Learned from the EU Referendum, there was no mention that Russia or any other nation or organisation interfered with the Brexit referendum, that is not to say social media did not play a role in amplifying misinformation.

Nearly half the UK believed that the UK paid £350 million a week to the EU, even after the figure was proven to be false. Voting to remain in the EU was the UK’s first digital referendum; with the leave campaign’s emotive message pulling in the voters via social media.

While the true extent of the role that Cambridge Analytica and Facebook played in the outcome of the 2016 US election is still a subject of much debate, this and the outcome of the EU referendum highlight the second flaw in the democratic process: algorithmic news.

Propaganda itself is part of the political ‘game’, but in 2016 we entered the new age of digital elections. Political advertising is now data-driven, with individualised adverts created by data scientists who micro-target specific ‘psychographic’ electorates.

After Facebook’s user data was used to ‘influence’ voters in the Trump campaign, the platform launched an initiative to assess social media’s impact on elections and democracy. Additionally, in a bid to protect the integrity of elections both Google and Facebook have rolled out new policies to authenticate advertisers and enhance transparency.

But will this really change anything? How DO you stop the personalisation of content? It is, after all, at the heart of social media’s appeal.

As far back as 2001, in his book Republic.com, Cass R. Sunstein talked about the perils of personalisation and social media’s potential as a threat to democracy. “The imagined world of innumerable, diverse editions of the ‘Daily Me’ is the furthest thing from a utopian dream, and it would create serious problems from the democratic point of view”.

This notion dovetails neatly into the third flaw: confirmation bias. This existed long before social media, which has only served to exacerbate the problem.

Researchers from Massachusetts Institute of Technology Harvard studied how people shared 1.25 million stories around the US election and concluded that social media had created a Breitbart-anchored self-reinforcing echo chamber.

Winning an election is far less complicated than we may believe and it can involve very small numbers of citizen-voters. Since the US elections were first held in 1824, winning is all about how the counting is done.

In the US, a few hundred voters in one state could swing an election. This was highlighted by the 2000 election battle between George W. Bush and Al Gore. The margin of 537 Floridian votes resulted in a Supreme Court decision that handed the presidency to Bush.

Time took a look at the 48 US presidential elections since 1824 and found three elections in which a few hundred voters in one state could have swung the outcome.

Trump’s 2016 presidential election was decided by about 77,000 votes out of than 136 million ballots cast in Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Michigan, states won by the smallest number of votes.

In our small island democracy with the ‘first past the post’ system, Theresa May’s Conservative Party might have had a full majority if 533 people had voted differently.

So, can we save democracy?

Maybe. Barack Obama once said “It would be completely transformative if everybody voted”, perhaps to turn the US’ democratic fortunes around voting should be made compulsory. It certainly might help with voter participation.

But 2016 was the year of long odds. In short, the probability of Leicester City winning UK’s Premier League (which was 5000 to 1) as well as the UK voting to leave the EU and Trump beating Clinton to become the 45th President could have won someone £4.5 million on a £1 accumulator.

Investment professionals in developed markets take certain things for granted. For a start, we all ‘assume’ that democracy cannot be gamed. And yet, what we have learned from the combined pronouncements of Cambridge Analytica and Mr Zuckerberg is that a relatively small number of electors can determine an election and their preferences are both knowable and open-to-influence.

We believe that we live in age that favours opportunism. Where improbable outcomes are all too likely. And where democratic processes aren’t what they seem. Does that seem consistent with low interest rates and implied volatility levels.

Omar Ayache

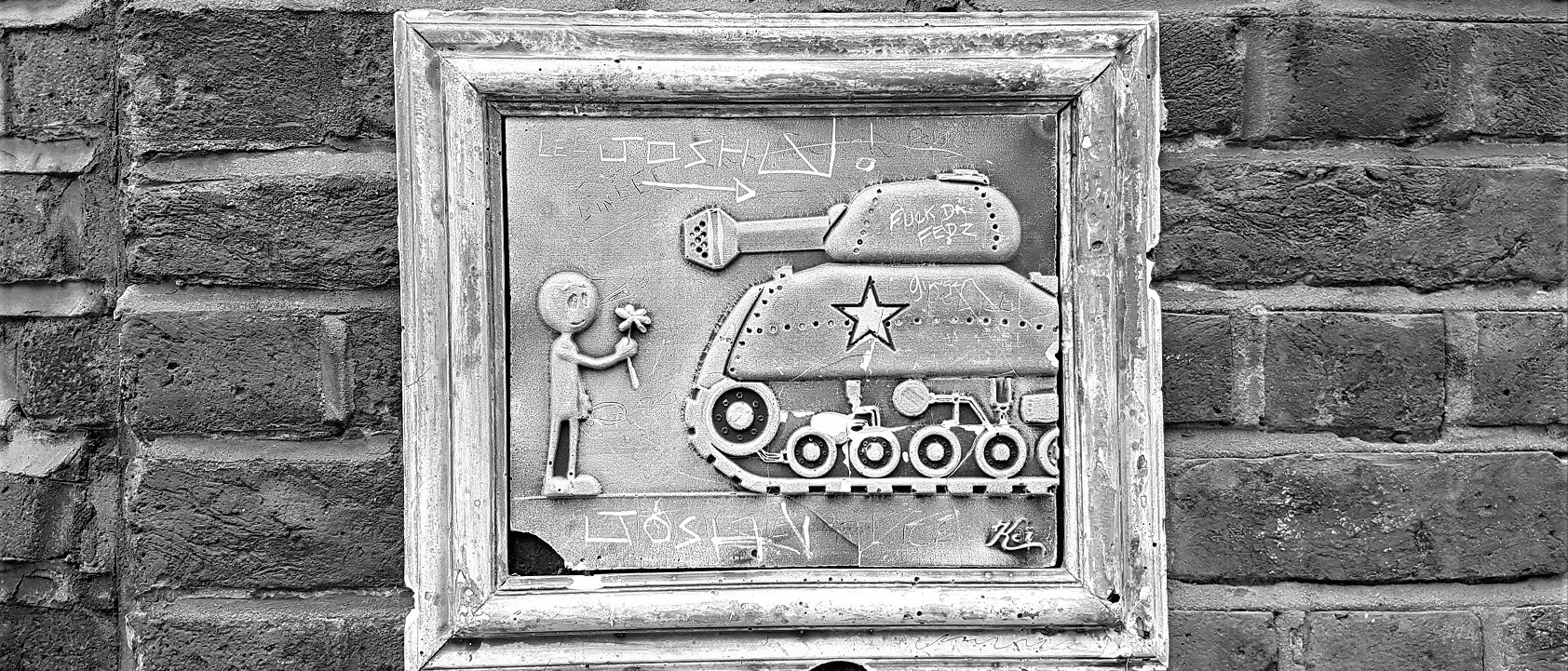

Photo: © Niki Natarajan 2017

Artist: Kai Aspire

¹ Questions over links between Cambridge Analytica and Emerdata (3.5.2018), Financial Times

² Brexit was not due to Russian dark arts (6.11.2017), Financial Times

Article for information only. All content is created and published by CdR Capital SA. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s). Information on this website is only directed at professional, institutional or qualified investors and is not suitable for retail investors. None of the material contained on this website is intended to constitute an offer to sell, or an invitation or solicitation of an offer to buy any product or service. Nothing in this website, or article, should be construed as investment, tax, legal or other advice.

Related articles

Siren Call

The British general election campaign was strange and dystopian. Punctuated by Islamist terror attacks and almost devoid of detailed debate on economic policy, the weeks leading to 8 June were dominated by a sense of weary resignation.

Populism Paradox

It doesn’t matter whether or not Trump wins on 8 November because the populism genie is out of the bottle. It is now clear that peak globalisation lies behind us.

The Age of Extremes

What kind of world do we live in? This is the most fundamental of investment questions. By this we typically mean “what is the outlook for inflation and economic growth?” Sometimes, the question is more socio-economic in nature. Rarely is it existential.