Peak Welfare

Share this article

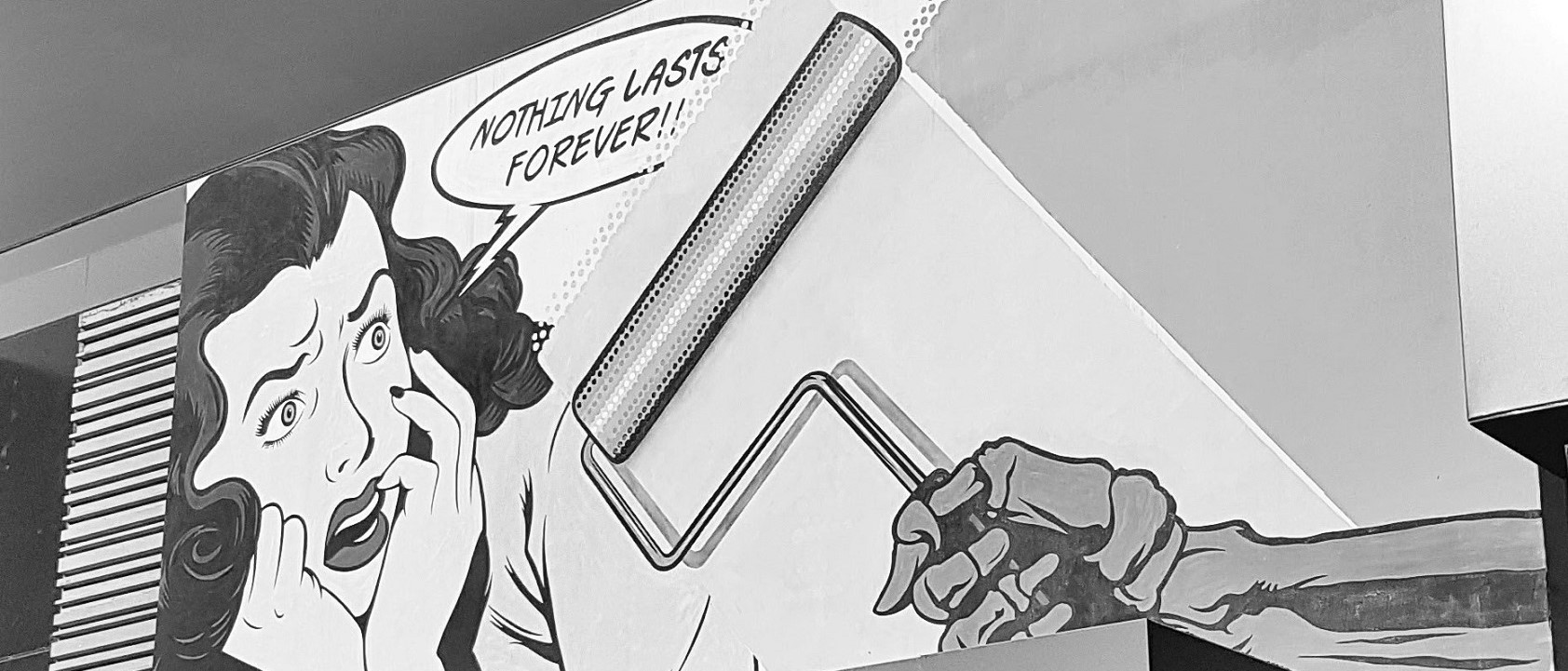

The unpalatable truth?

“When I look at the current picture of expected tax revenues combined with benefits promised to future generations, this is the most unsustainable situation I have ever seen in my career” ~ Stanley Druckenmiller

The welfare state today is not fit for purpose. Its architects had not conceived it for a world of 90-year longevity, mass migration or a low interest rate environment. The mathematics of ‘Baby Boomers’ retiring plus low birth rates just does not add up.

In Europe, peak workforce was passed in 2010. By 2060, the dependency ratio of the EU is projected to increase to 50.1% (from 27.8% in 2013), according to the European Commission’s The 2015 Aging Report.

And as living to 90 does not guarantee a healthy life, adding healthcare subsidies to pension pressures in countries with the highest oldest populations is only likely to detonate the demographic time bomb sooner.

It’s not just a European problem. With 33.1% of the population aged 60 or over in 2015, Japan has the oldest headcount. By 2060, there will be 1.3 Japanese aged between 15 to 64 for every person over 65, a situation made worse by the near absence of immigration¹.

In the developed world, there could be two billion people aged 60 or over by 2050, say UN estimates. Stanley Druckenmiller, an advocate of reducing entitlement spending, says the numbers in the US don’t add up either. The US’ Social Security’s trust funds will be exhausted in 2029, per Congressional Budget Office projections.

As the labour force shrinks, demand decreases and economic growth falters. Demographics in the US will drive a ‘new normal’ of low investment, low interest rates and low output growth, according a Federal Reserve report.

Understanding the New Normal: The Role of Demographics states that “demographic factors alone account for a 1.25% decline in the natural rate of real interest and real GDP growth since 1980.”

As population asymmetry grows, something needs to give. Real solutions, however, are likely to require political tough love. “We all know what to do, we just don’t know how to get re-elected after we’ve done it,” said Jean-Claude Juncker, President of the European Commission in 2007.

In The Welfare State in Europe: Visions for Reform, Iain Begg, Fabian Mushövel and Robin Niblett ask, “What is the extent of the state’s responsibility to its citizens and specifically whether governments can or should maintain comprehensive welfare systems in the future?”

This is the battle newly elected Donald Trump could end up having with Paul Ryan, speaker of the House. Trump may have promised not to cut healthcare and social security benefits during his campaign, but entitlement spending was about 48.7% of all government spending in 2015.

It is going to be a difficult promise to keep when there are 10,000 Baby Boomers turning 65 every day. So what options are there to defuse this ticking demographic time bomb and how will it impact the economy?

Wielding Geddes Axe—severe public spending cuts introduced by Sir Eric Geddes in 1920s Britain—is one solution. Increasing taxes is another. Neither will be popular with voters. A shrinking workforce also means the number of tax payers is decreasing.

What else? Finland and France are finding ways to encourage larger families, while UK is planning to raise retirement age. With 39% of the population projected to be over 60 by 2050², German industry has been taking this problem seriously.

Above inflation wage rises, subsidised meals, an onsite nursery, training for older workers and flexibly working are Knipex’s way of combating an aging workforce. In 2007, BMW started tackling the problem of the older workforce expected a decade later, at a time when the average age of its workers was 39.

In India and China, the demographic time bomb is different. A cultural preference for males in both countries has resulted in what the Chinese call Bare Branches; more males per 100 females. Despite reversing the policy last year, the demographic effects of China’s one child policy³ will take a very long time to change.

Angela Merkel, known for her almost accurate summary of the peak welfare problem—“Europe today accounts for just over 7% of the world’s population, produces around 25% of global GDP and has to finance 50% of global social spending”—has also road tested a potential solution: immigration.

Despite teething problems and revising the strategy to impose a five year ban4 on benefits for jobless migrants, the need for skilled migrants has not gone away. According to a report Immigration: Encourage or Deter? migration could boost the UK economy by £625 billion (or 11.4% bigger) by 2064-65.

Modern politicians are faced with an unusual situation; the need to tell the unpalatable truth rather than the plausible lie. In the case of peak welfare, this means making genuinely ‘hard choices’. Do governments drastically cut welfare, defense spending and healthcare, or do they increase taxes, borrowing or immigration?

Photo: © Niki Natarajan 2016

D*Face (Dean Stockton)

¹ Age Survey underlies pressures on Japan (29.5.2016), The Financial Times

² Germany’s Demographic Dilemma (16.11.2016), The Financial Times

³ The most surprising demographic crisis (5.5.2011) The Economist

4 Germany plans 5-year benefit ban for jobless migrants (28.4.2016) The Financial Times

Article for information only. All content is created and published by CdR Capital SA. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s). Information on this website is only directed at professional, institutional or qualified investors and is not suitable for retail investors. None of the material contained on this website is intended to constitute an offer to sell, or an invitation or solicitation of an offer to buy any product or service. Nothing in this website, or article, should be construed as investment, tax, legal or other advice.

Related articles

We are all socialists now

The political left is always tempted to think that it is about to win the war. After the global banking crisis in 2008 fevered left-wing analysts concluded that a crisis in capitalism would mean a leftwards shift in politics. Could they now be right?

Siren Call

The British general election campaign was strange and dystopian. Punctuated by Islamist terror attacks and almost devoid of detailed debate on economic policy, the weeks leading to 8 June were dominated by a sense of weary resignation.

The Age of Extremes

What kind of world do we live in? This is the most fundamental of investment questions. By this we typically mean “what is the outlook for inflation and economic growth?” Sometimes, the question is more socio-economic in nature. Rarely is it existential.