Race to Zero

Share this article

The Heat is On

“As for the future, your task is not to foresee it, but to enable it” — Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

The heat dome over the usually ‘moderate’ climate of the Pacific Northwest that has so far killed more than 700 people in British Columbia (and ‘cooked’ one billion sea creatures), and Europe’s catastrophic floods that have taken the lives of more than 200 people, are breaking records.

Chinese provinces have even had to ration electricity as air conditioning use rises, highlighting one of the great ironies of climate change. The seven hottest years on record have happened since 2014, but it is the excessiveness of 2021’s record-breaking numbers that begs the question: has anthropogenic climate change reached tipping point?

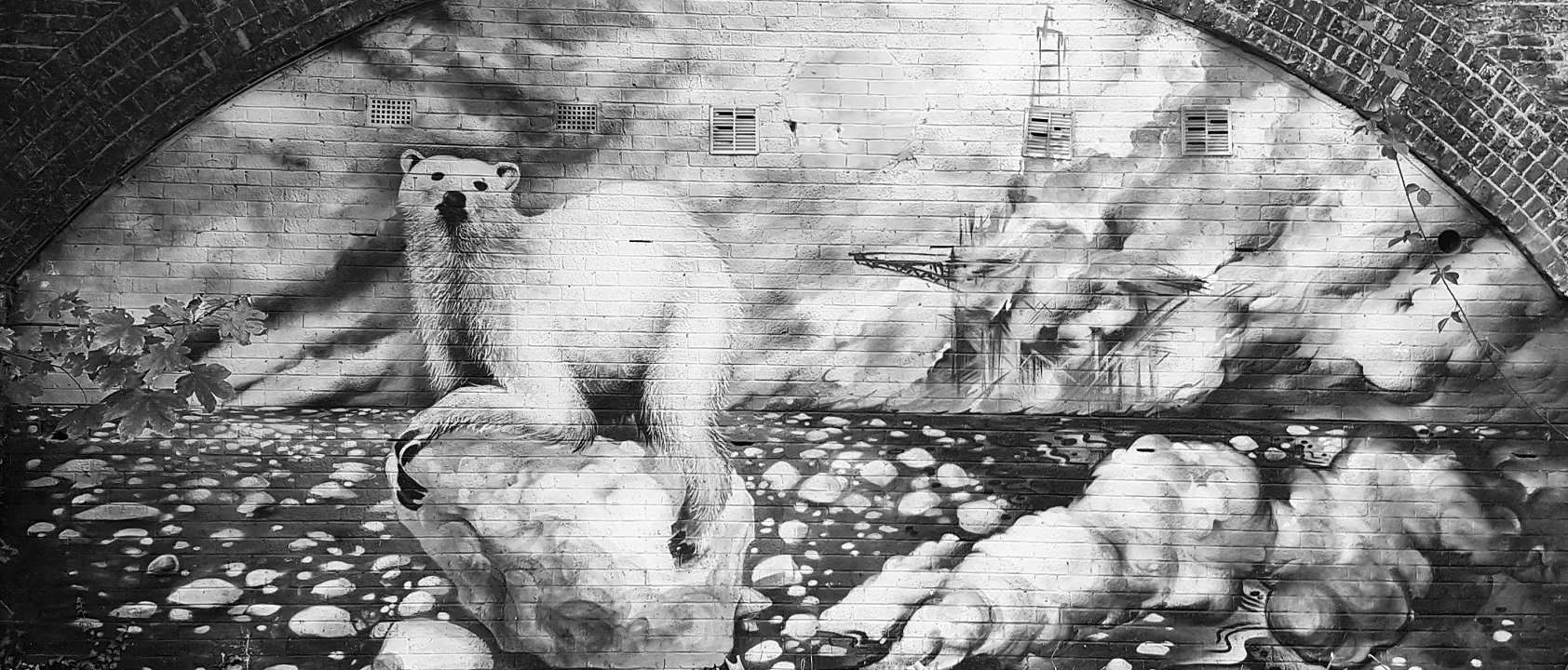

With continued rising temperatures come melting polar caps and changes to ocean currents in a vicious circle that some experts say could culminate in sea levels rising by one metre by 2100. In this scenario, 40% of the world population would be affected and global hubs such as New York, London, Miami, Tokyo and Jakarta could all be submerged.

Scientifically, all of this was predictable. The knowledge dates back to 1824, when mathematician Joseph Fourier postulated the idea of the atmosphere as an insulator; a notion now known as the greenhouse effect. In 1896, Swedish scientist Svante Arrhenius suggested that the carbon dioxide released by burning fossil fuels would raise the planet's average temperature.

But it was in 1988, in a testimony to the US congress that James Hansen, administrator at NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, presented evidence that the earth’s climate was warming and that humans were the primary cause. The US is the second largest CO₂ emitter and a country where ‘climate science denialism’ is particularly rife and partisan.

Moreover, the oft-derided climate models that have been tracking CO₂ levels and signalling global warming since 1973 seem to be remarkably accurate. So why are governments only now waking up? Could it be that ignoring the climate crisis could cost more—$150 trillion and $792 trillion by 2100—than the $16 trillion to $103 trillion to do something about it?

The pandemic has given us a glimpse of what a pollution-free world could look like, and, perhaps more importantly the sense that we can do something about it. On the surface, many of the world’s post pandemic economic stimulus packages are touting a ‘green’ recovery.

But last June, Bloomberg calculated that only 0.2% of the roughly $12 trillion¹ in stimulus packages had been targeted towards climate priorities. As Paris Climate Agreement net zero pledges start coming in ahead of COP26 in Glasgow later this year, will the energy transition and race to net zero be too little too late?

Right now, more than 65% of global carbon dioxide emissions, and more than 70% of the world economy have made ambitious commitments to carbon neutrality. Japan and the Republic of Korea, together with more than 110 other countries, have pledged to be carbon neutral by 2050, while China, the largest CO₂ emitter, says it will do so before 2060.

At the start of the year, Joe Biden’s administration reversed Trump’s decision and the US re-joined the Paris climate pact. Biden plans to reduce greenhouse gases to by 2030 50% to 52% from 2005 levels, create well paid union jobs and help the US take a leadership role on clean energy technologies.

In a bid to become the first climate neutral continent by 2050, the European Commission has just released its latest version of the European Green Deal dubbed ‘Fit for 55’ that sets an ambitious target of a 55% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 (relative to 1990 levels). Among its aims are to create 160,000 green jobs, renovate 35 million buildings and increase the natural carbon sink target to 310 mt.

Not to be outdone in a post Brexit world, the UK set into law the world’s most ambitious climate change target, namely to cut emissions by 78% by 2035 compared to 1990 levels. And, for the first time, UK’s Carbon Budget will incorporate the UK’s share of international aviation and shipping emissions, which will bring the UK more than three-quarters of the way to net zero by 2050.

A Two-Pronged Approach

Strategically, to limit global warming to below 2°C, preferably to 1.5°C compared to pre-industrial levels by the 2050 deadline, requires a two-pronged approach. The first is the creation of alternative sources of renewable or at least sustainable power including solar, wind, biomass, hydro, geothermal, and hydrogen to replace fossil fuels.

The second is to capture and store existing excess carbon in the atmosphere. Through the carbon sequestering capabilities of trees, soil and oceans, the earth has homeostatic mechanisms to reach ecological balance. Natural solutions to support nature include mass tree planting (deforestation contributes to CO₂ emissions so not cutting down trees could cut annual emissions by about 10%) and regenerating marine ecosystems.

Oceans are the world’s largest carbon sinks, storing what is called ‘blue carbon’. Coastal habitats may only make up 2% of the total ocean area, but they account for roughly half of all the blue carbon sequestered in ocean sediments.

And seaweed has become a serious climate change protagonist for its carbon dioxide absorbing capabilities, role in bioplastics and as an aviation biofuel. The value seaweed cultivation market was valued at $16.7 billion in 2020 and is projected to reach $30.2 billion by 2025, a CAGR of 12.6%.

Artificial carbon capture and storage (CCS) processes have been used in the oil and gas sector for years. CCS involves separating CO₂ from other gases as they exit chimneys by using specifically designed chemicals. This removes about 90% of the CO₂ emitted, and represents about 70% of the overall cost of carbon.

In an interview with New York Magazine, Vaclav Smil, one of Bill Gates’ favourite authors, says carbon sequestration is “just simply dead on arrival”. His argument is scale and that just 10% of the CO₂ produced is the same volume as the crude oil produced, an industry that took 100 years to develop.

And while CCS has yet to be deployed at scale at power plants, cement works or for steelmaking the impetus is there. At the start of the year, Elon Musk launched the XPrize Carbon Removal competition to produce a device that can remove one gigaton – one billion tons – of CO₂ from the earth per year.

Technology to remove carbon dioxide from the air, known as direct air capture (DAC), is also in the works. Swiss start up Climeworks is developing this technology, while Carbon Engineering’s prototype is about to become operational in Canada later this year, with another planned in Texas.

For a while, bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) was considered the ultimate climate solution, but it required mono culture, vast amounts of water, as well as the use of 0.4 to 1.2 billion hectares of land, 25% of the 80%, currently under cultivation for food.

In his 2019 book Growth: From Microorganisms to Megacities Smil highlights his concern that renewables such as biofuel crops, solar parks, and wind farms could potentially take up 100 or even 1000 times more land area than current energy production with negative impacts on agriculture, biodiversity, and environmental quality.

Financing the energy transition

Financing the energy transition at pace and scale is critical. A panel at the recent World Economic Forum’s Green Horizon Summit suggested that it would take 1.5% of global GDP to fund a clean energy transition.

In the last few years, asset owners and now investment managers have started to realise that climate risk is an investment risk, as well as an opportunity and many are aligning their portfolios with the relevant UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Affordable and Clean Energy (SDG 17) and Climate Action (SDG 13).

In fact, at the recent CERAWeek conference, Ben van Beurden, Shell’s chief executive officer, said "Net zero is both a moral imperative and an amazing business opportunity". Despite many investors being burnt the first-time round, Clean Tech 2.0 is here to stay, so much so that Climate Tech is a venture capital subset on its own.

Right now, while the climate tech numbers are compelling, they are still not large enough given the scale of the challenge: $60 billion (2013-2019); 84% compound annual growth rate (3,750% over the seven year period); 1,200+ start-ups identified; and $16 billion invested in 590 deals in 2019.

That could be changing if the latest raft of launches are anything to go by: Amazon’s $2 billion The Climate Pledge Fund; Microsoft’s $1 billion Climate Innovation Fund; and Unilever’s €1 billion Climate & Nature Fund.

Breakthrough Energy Ventures—led by Bill Gates and backed by Jeff Bezos, Richard Branson, Reid Hoffman, Jack Ma and Michael Bloomberg—has raised its second billion² to invest in 40 to 50 start-ups across themes such as climate-friendlier steel and cement production and long-haul transportation.

Committing to Net Zero

Investors have been leading the decarbonisation charge by divesting from fossil fuel companies since 2008. Some 1327 institutional investors, including Ireland, New York City and the Norwegian Sovereign Wealth Fund, have committed to divesting $14.58 trillion to date. Now they optimising portfolios by removing big emitters, and tilting towards energy transition winners.

Under the banner of The Net Zero Asset Managers initiative, 128 asset managers, with $43 trillion in assets under management—almost half the $100 trillion under management globally—have committed to a net zero target with Amundi, Franklin Templeton, Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Asset Management and HSBC Asset Management, the latest to join.

And, despite 60 of the largest banks collectively financing fossil fuels to the tune of $3.8 trillion between 2016 to 2020, the five years after the Paris Agreement was signed, banks are stepping up to the plate too. On her first day as chief executive officer earlier this year, Jane Fraser vowed Citigroup would achieve net-zero greenhouse-gas emissions in its financing activities by 2050.

A month later, 40 plus banks signed up to be part of Net Zero Banking Alliance. There are now 53 banks from 27 countries representing $37 trillion of banking assets committed to aligning their lending and investment portfolios with net-zero emissions by 2050.

On a corporate level, firms such as Nestlé, Repsol, Qantas, ThyssenKrupp, BP, Ford Motor Company, American Airlines, CEMEX and Woolworths are also committing to net zero. Not only that at least half of the world’s biggest companies are now factoring the cost of carbon into their business plans, cognisant that it will eventually affect their stock price.

The Energy Impact Partners’ Climate Index has been up 127% compared to 45% for the NASDAQ since the start of 2020. Clean tech valuations, however, are still completely out of synch with profits, highlighted by Fuelcell Energy that has seen its market value soar by 800% in recent months to reach $5.6 billion³, despite not reporting an annual profit in 20 years.

At the same time, the oil majors are stuck in a Catch-22. Some well-known oil and gas companies saw their market capitalisations halved in the first nine months of 2020, despite many—largely European groups such as Total, BP, Royal Dutch Shell, Equinor, Eni, and Repsol—investing in low-carbon businesses including wind turbines, solar panels, and hydrogen. Shell aims to become a major player in biofuels, nature-based solutions and carbon capture and storage.

Despite this, BP, Shell, Repsol, Eni and Total saw losses of 50% plus in 20204. Clean techs are typically valued on future earnings, while oil companies on ability to pay dividends, so one solution may be that oil and gas firms spin off their renewable businesses when they achieve scale to realise value.

In 2019, the total new investment in renewable energy alone was more than $300 billion globally, a 2% increase from the previous year. Globally, solar and wind are now the cheapest forms of energy available, the former thanks in part to a rapid expansion of Chinese production of solar panels.

And, if Goldman Sachs is right, green hydrogen could become a $12 trillion market. A year ago, the European Commission published its 2030 hydrogen strategy where it outlined total investments of up to €400 billion through 2030, with up to €47 billion just toward electrolysers required for green hydrogen, even though it is still two or three times the cost of grey hydrogen. A truly sustainable and far cheaper energy source is natural, or white hydrogen, whose potential is the latest clean energy pathway being explored.

Moreover, the Biden administration has committed to a 100% carbon-free grid by 2035, and through the RE 100, nearly 300 global companies have made similar commitments to use 100% renewable electricity. Microsoft, who plans to use zero-carbon energy by 2030, is also changing the way it buys its electricity.

But the energy transition is about more than just generating clean energy; thematically investors can access it through energy storage for example; essential for the growth in electric vehicles. General Motors and Volvo announced plans to sell only net zero emissions cars in the next decade, and Norway, whose wealth is based on fossil fuels, became the first country in the world where the sale of electric cars overtook those powered by petrol, diesel and hybrid engines.

But a darker side to the electric vehicle revolution is what will happen to the dead batteries. Unlike their lead-acid ancestors that are readily recycled, the lithium-ion versions used in electric cars need to be dismantled carefully or they explode, so only about 5% are currently being recycled, with Nissan, Renault and Volkswagen among the trailblazers.

Not only electric vehicles, but also wind farms and solar power will require about five times as much copper as typical electrification networks, and so key minerals and metals such as cobalt and nickel can offer investment opportunities with a caveat that mining has the potential for further environmental damage.

John Kerry, US Special Presidential Envoy for Climate, believes that half of all reductions in carbon emissions will need to come from technologies that have yet to be invented. Meanwhile Vinod Khosla believes clean energy technology could create companies as profitable as Google, Apple and Facebook (all of whom have also become big investors in clean energy).

In his book The New Climate War: The Fight to Take Back Our Planet, Penn State climatologist Michael Mann argues that public policy needs to be the driving factor not more innovation. Former governor of the Bank of England and UN special envoy for climate action, Mark Carney, agrees. He recently urged that businesses should be regulated arguing that the climate crisis and with it the bio diversity crisis is too large and too systemic and too existential to be left to the free market.

But is it all enough to achieve the goal in time? While the pandemic curbed CO₂ emissions temporarily, the world needs to see the emissions fall by 7.6% per annum between 2020 to 2030, if there is any hope of reaching the Paris climate target of 1.5°C.

Like its predecessors, the fourth energy transition from fossil fuels to renewables is more complex that simply a shift from one energy source to another: wholesale energy transitions impact businesses, jobs, industries, economies and societies.

The inconvenient truth is that the fossil fuel-driven growth will be hard to decarbonise because, even though it is beginning to decouple, there has been a strong correlation between GDP and energy use. Managing this transfer without killing the economy is harder than it looks even for small companies. Analysing our own tiny footprint in a business where our clients and investments (both of which need to be visited in person) are global has been an eye opener.

One of Smil’s most relevant observations is how long the fourth energy transition might take given the billions of tonnes of fossil fuels the world still consumes each year. Right now, despite producing more energy from renewables each year, the global energy mix is still 84% from oil, coal and gas, wind and solar are just 3.3% together.

As we withdraw from extractive-industries it is worth asking the questions no-one wants to ask: what is the carbon footprint of wind turbines or solar panels compared to fossil fuels, for example?

The difference between them is that the emissions of wind and solar are front loaded in the creation of steel (some 30% of the carbon impact), mining of metals and manufacturing of concrete, while fossil fuel power plants, the emissions are for the life time of the plant.

When the lungs of the planet are producing more carbon dioxide than they are absorbing, the hands of the Doomsday Clock might have less than 100 seconds to midnight by January 2022, but let’s make sure that our long-term ‘sustainable’ choices don’t have unintended social or environmental consequences.

Photo: © Niki Natarajan 2017

Artist: Jim Vision

¹ How to Grow Green, Bloomberg (9.06.2020)

² Bill Gates-Led Fund Raises Another $1 Billion to Invest in Clean Tech, Bloomberg (19.01.2021)

³ No-Name Clean Tech Firms Are Turning Into Billion-Dollar Bets, Bloomberg (19.01.2021)

4 European oil stocks dealt €360bn blow while renewables surge, Financial Times (29.10.2020)

Article for information only. All content is created and published by CdR Capital SA. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s). Information on this website is only directed at professional, institutional or qualified investors and is not suitable for retail investors. None of the material contained on this website is intended to constitute an offer to sell, or an invitation or solicitation of an offer to buy any product or service. Nothing in this website, or article, should be construed as investment, tax, legal or other advice.

Related articles

Pollution

Mount Kenya visible Nairobi and some of the most polluted waterways are running clear. The Great Lockdown’s silver lining has been a drop in air pollution and increase in water quality. Is choosing between the economy and our collective health right?

Rare Earths

When President Trump tweeted about his bid to buy Greenland it was not fake news but about smartphones and electric cars. The world needs rare earths for rechargeable batteries, catalytic converters and wind turbines, who will dominate this market?

Investor Activism

An 18-year-old asks academics and veteran finance-industry alumni when will the college’s endowment disinvest from fossil fuels? A year later, the foundation was carbon neutral. Being socially and environmentally conscious is a risk-mitigation strategy.